When OpenAI chief Sam Altman was asked what he hoped Artificial General Intelligence would do, he mentioned solving the Grand Unified Field Theory of Physics, and whether the universe holds other intelligent life. Which is to say, if and how the universe coheres, and whether our strange consciousness is part of its design, or whether we’re some kind of weird fluke.

Those have been The Big Questions pretty much since humans showed up. Today AI is a plausible skeleton key to reality, since it’s made out data and math, our current gold standards for truth. Some of our best thinkers see reality itself as math. So why shouldn’t AI have a shot?

Thing is, we had what we thought was something like a skeleton key 600 years ago, when Linear Perspective started accurately depicting space through geometry. Almost immediately, this radically new kinds of painting and sculpture emerged, with implications about the solitary self relating to God that predated the Protestant Reformation by a century. Perspective took us through stages that created Western Science itself, elevating math towards its current supremacy. Along the way there were some very Altman-esque obsessions about what this triumph of math might be that serve as a healthy check to today’s wildest imaginings.

Perspective spread quickly from the early work of Brunelleschi, Masaccio, and Donatello. The next great acolyte was Paolo Uccello whose lover yelled at him to stop playing with perspective and come to bed. His great paintings model his obsession.

In this Battle, the violence of the lances and the foreshortened horses are perspective techniques move our eyes past the core violence, to a lesser chaos of noblemen in close battle, and finally in to a passive background where lone man hunts rabbits. Like lots of 600 year-old art, it’s hard to say what that means, but the math obsession is clear.

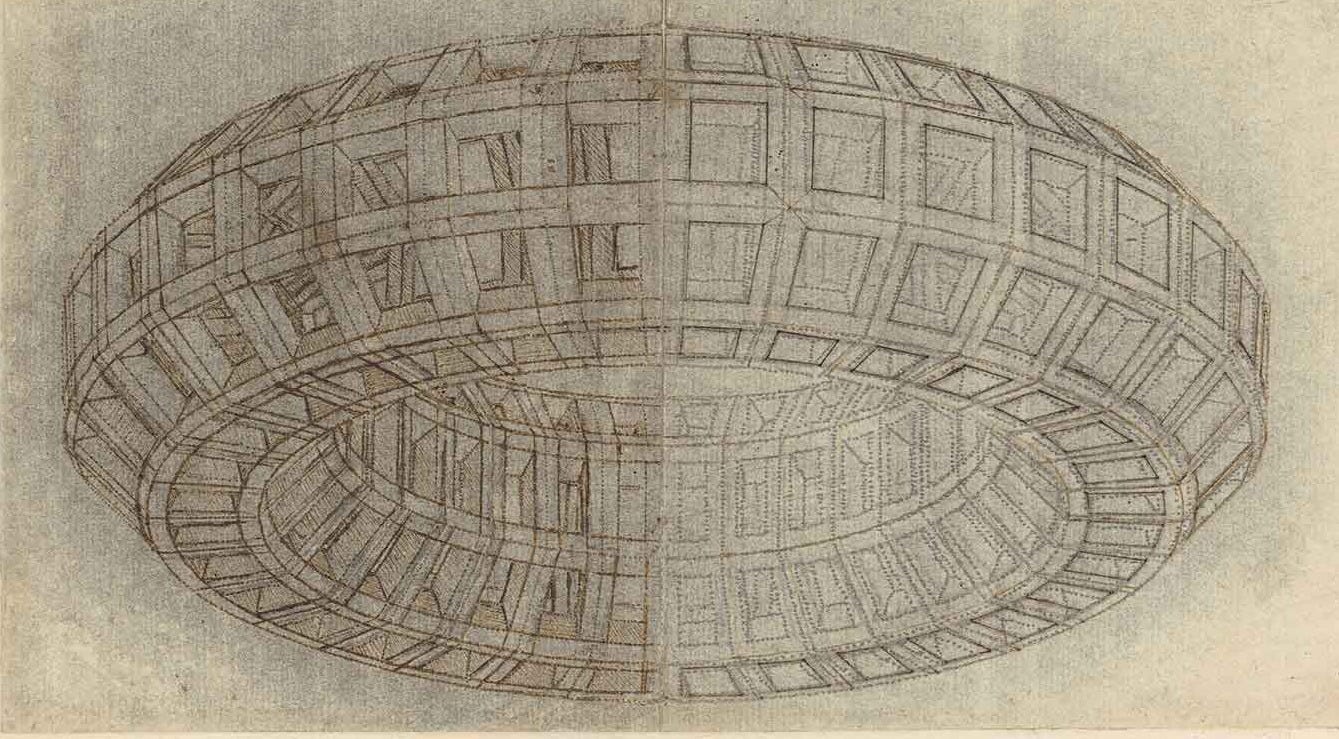

The fighters are wearing a mazzocchio, the polyhedron-styled hat worn by wealthy men in Uccello’s Florence. Once you start looking at Uccello you see this headgear everywhere, like this picture, where for some reason a son of Noah is wearing one like a necklace:

Making this shape from several angles, in paintings, drawing, or wood inlay, became a means to showing one’s perspective chops for another 150 years, long after the hat was out of style. Da Vinci, passionate about understanding the visual world 50 years after Uccello, was particularly adept.

This study of the geometry of reality was something like our counting and systematizing data (the heart of AI) is today, with religious implications. Perspective was a way of studying and celebrating creation by noticing and depicting all its glory (quite a change from the dour Medieval view of this world of sin and trouble.) The new oil paint from North Europe, another refined technology, allowed for even more detail.

Sam Altman is in a more secular age, and his ambitions for math are likewise secular (though no less interested in piercing reality.) This was an extensively Christian era, and one painter took math far into his devotion.

Piero della Francesca illustrated newly-recovered texts on geometry by Archimedes before he took off as a painter. He wrote for private consumption three mathematical treatises of his own. (1) His passion for the art of math and the math of the art, twin manifestations of God, are stunning theology.

Take this “Baptism of Christ,” c. 1437-45:

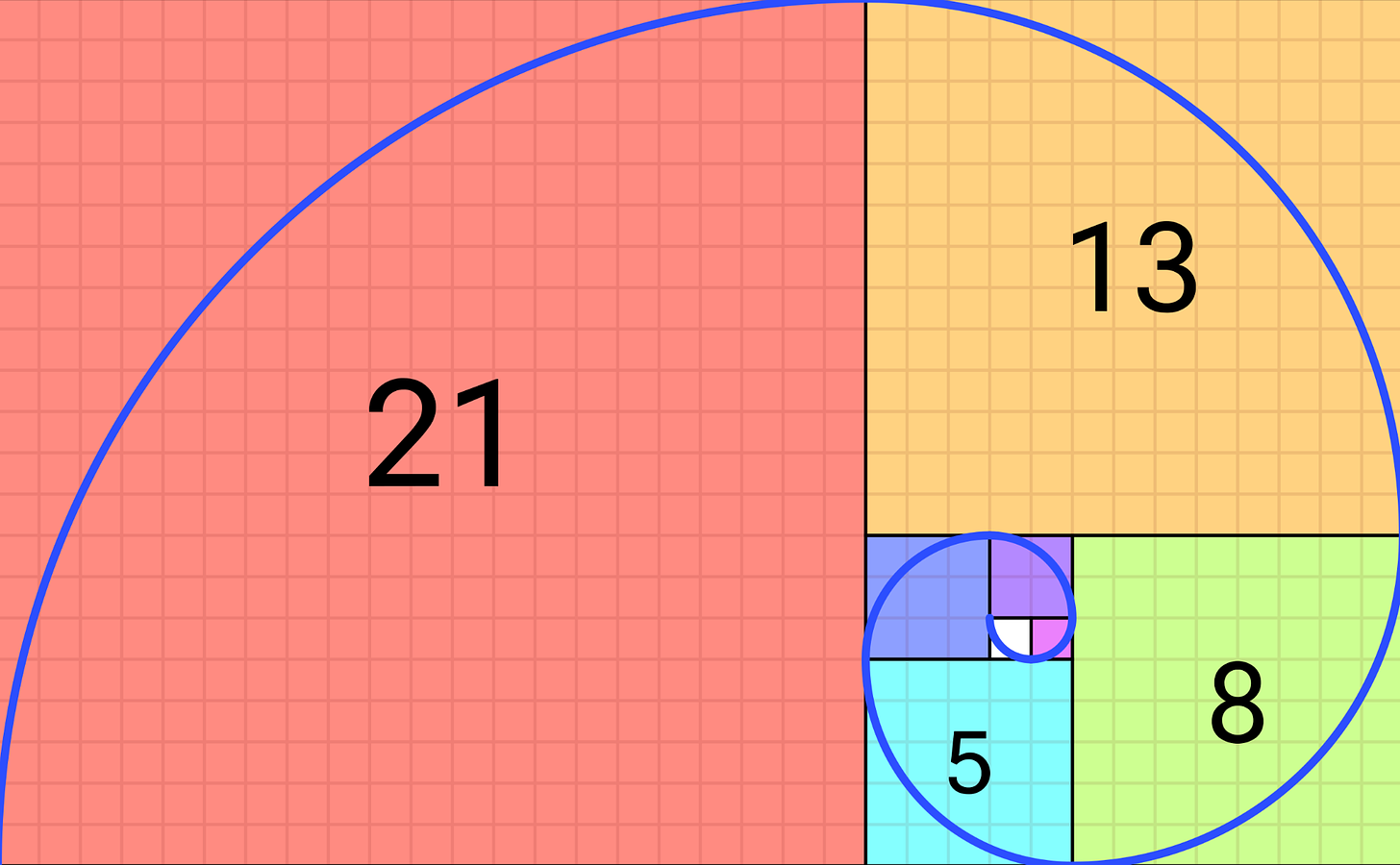

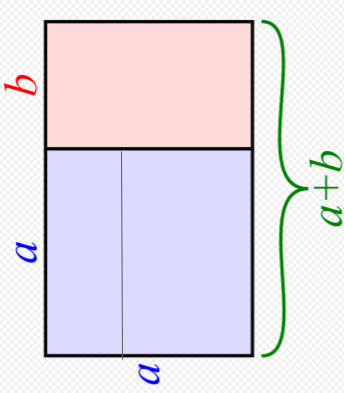

If you draw a rectangle from the tree next to Jesus and down from the dove, you get a “golden section,” or an infinitely repeating pattern of a rectangle and square, like these:

He’s portraying the first manifestation of the Christian holy Trinity. A human Christ undergoes baptism, as (according to Matthew 3:16) God says “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased,” and the holy ghost, a dove, flies overhead. By putting Jesus at the center of an eternal perfect shape, he’s showing an eternally perfect trinity.

We’re used to this kind of thing in Kabbalistic reckonings, Mayan calendars, and Hindu calculations, and other math-based ways of divining the eternal. Piero isn’t just using math to depict the world, he’s saying that math is a the heart of the world, and God’s infinitude can be depicted in mathematical ways. This is resonant in ways he couldn’t have known; today we see Fibonacci curves in pineapples, artichokes, shells, and the shapes of galaxies, among other things. (2)

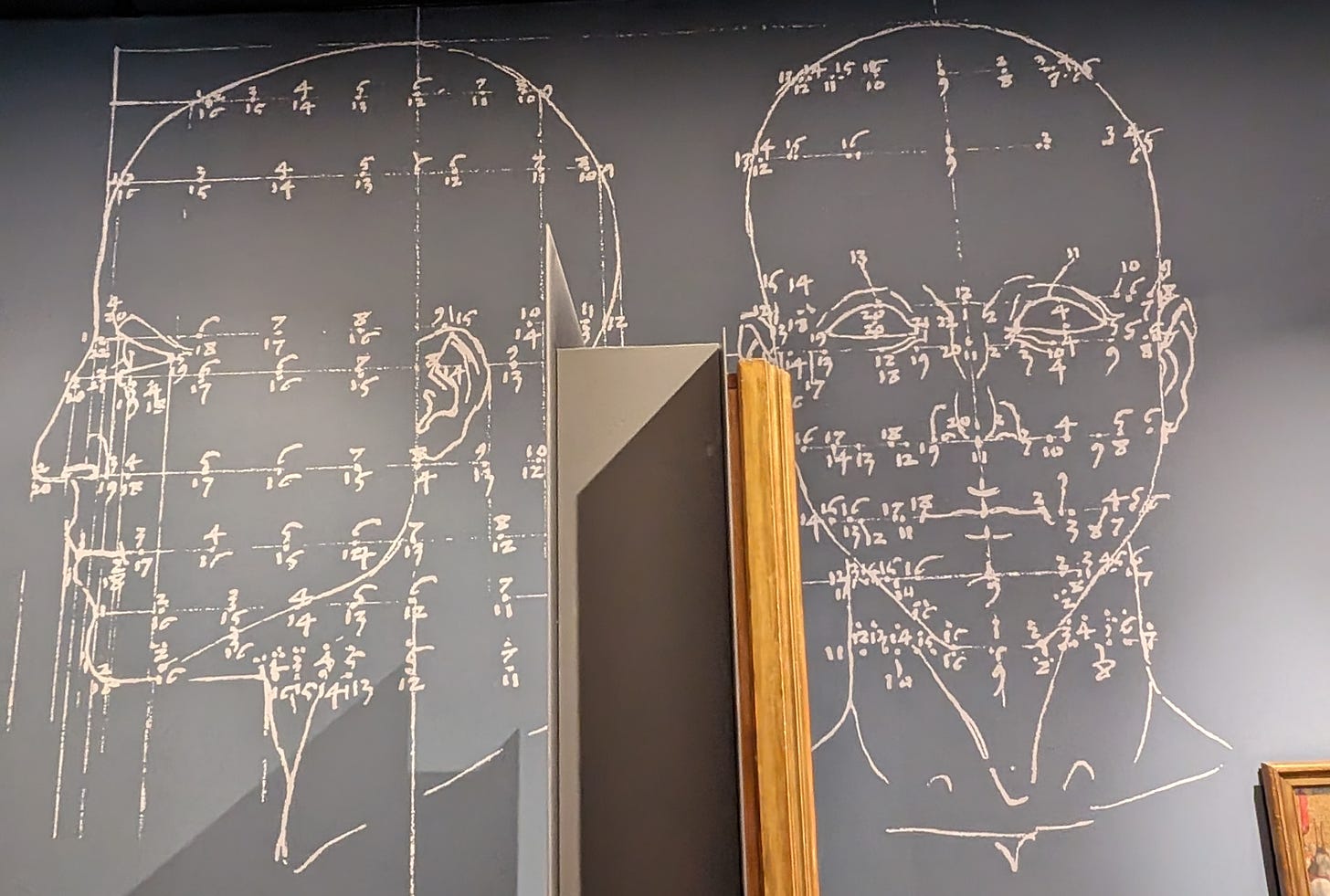

It’s also the problem with the emotional distance of art for many viewers, including me. Piero developed a way of mathematically determining all of the coordinates of the human face, so you could accurately depict someone from any angle:

He often painted subjects in layers and blocks, painting an arm and then painting a sleeve over it, making the work a little more “mathy” than fully human (3). Da Vinci, working just a little later, did the geometry work and filled notebooks with the emotionally rich faces of ordinary people he’d pass in the street, building a base of analytic understanding with something inexpressible, yet utterly human. His genius for the world in full is what makes him stand out.

It’s a dilemma we face again today, when we imagine AI taking us into a robotic future, even our human overlords somewhat robotic in their relentless devotion to the data and the algorithm.

Altman believes that the understanding of reality itself can be discerned from our existing data sets. It’s a presumptuous idea that what humans collect includes the key, when we barely consider, say, the vision of a bee or the sensory input of a walrus’ whiskers in contemplating the whole of the world. Everything is so much more than what we think we possess.

Who knows, though? Perhaps some new humanist genius waits in the wings.

Next: Rules and Reason.

We only know about Piero’s books because the work was “used without attribution” by Leonardo da Vinci’s best buddy, a friar and mathematician named Luca Pacioli in a book he published late in the 15th. Century

That’s him, with a copy of Euclid and a couple of Archimedean solids. Luca also described the double-entry bookkeeping system in use in Italy, creating the first standard textbook on the subject, a primary source for many decades. The British Library has an interactive view of a couple of his books, with da Vinci illustrations.

Once you get the golden ratio going, it’s hard to know where to stop. Check out this one, for Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (c. 1486.)

Apparently it would work even better if the panel hadn’t been trimmed slightly. Who knows?

You can’t deny Botticelli, who became an extremely devout person towards the end of his life, reveled in annotating creation in all its variety: His Primavera includes 500 plants, including 190 different types of flowers, 130 of which have been identified.

No knocking Piero’s skills, though. This painting was to go in the Duke of Montifeltro’s burial chapel:

Detail, San Bernardino Altarpiece, Piero della Francesca, c. 1474. Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan. Author photo. The armor in that shoulder “reflects” perfectly the church surrounding the chapel where the painting would be located. The dead Duke would be praying in Heaven, yet there with you. Chops!

I wrote something very much in the same vein for a discarded draft for a client... but you went quite deeper and I really enjoyed this.