The Eye & The Line, 1: A Man In A Square

The Age of AI has a lot in common with a 600 year old math-based revolution.

I’ve written about the way our fetish for precise measuring and counting was a cornerstone of the modern. All that counting enabled today’s AI revolution. This brief series will examine the time that a math-based arrangement of the world changed many more things than AI will likely change. It’s an astonishing story in itself, and offers clues about where we are headed now

This revolution was based on Linear Perspective, a working out of the geometry of optics that makes it possible to see a three-dimensional image in a two-dimensional picture. It became a cornerstone of Western art in the 15th Century. Indeed, for some people at the time it was as much a near-mystic development as the prospects of AGI and Synthetic Biology are to some people in our time.

Like much else in the history of technology, precursors and indirect causes influenced the development of Linear Perspective. In 11th Century Cairo, the Arab mathematician Abu Ali al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, known as Alhazen, composed a seven-volume treatise on optics. He wrote about mirrors, rainbows, and perspectiveal effects. He was read, and renowned by scholars, in the Islamic Nasrid Kingdom (now Spain’s Andalusia), where his book was translated into Latin around 1200, and into Italian about 100 years later.

* (the cool kind.)

Alhazen’s perspective was only a theory about perception, though, and not an application of the phenomenon. It’s easy to understand why his theory didn’t influence Islamic Art, since in Islam imitating the work of God in such a real-seeming way borders on arrogant blasphemy. (2)

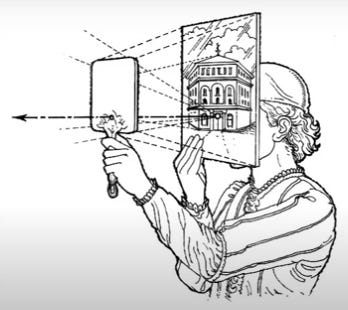

In about 1420 in Florence, Italy, an indefatigable thinker and maker named Filippo Brunelleschi (1) took the idea into the physical world. Brunelleschi stood in front of the city’s cathedral, facing the baptistery.

He held a mirror and a picture of the baptistery, with a hole in its middle. This image, now lost, was drawn in such a way that there was a horizon line and a vanishing point at the center, which was also the eye hole. A viewer could look at the baptistery, then look through the picture, and staring at the mirror held up to the picture with the other hand, and see the baptistery again, in three dimensions.

It seems simple now; after centuries we have become used to this kind of faux realism (AI deepfakes aren’t so new, they’re just a little better and a lot easier to create.) But at the time it was a breathtaking new view of reality.

Brunelleschi’s friends quickly picked up on his discovery. It rapidly changed not just the work of making art, but what Art might say about our ideas of God and reality. Within a few years, pictures changed. They had been two-dimensional, somewhat distant embodiment of saints and church stories. Now they were closer to holy visions that people might see with their own eyes. It was Virtual Reality, 1440.

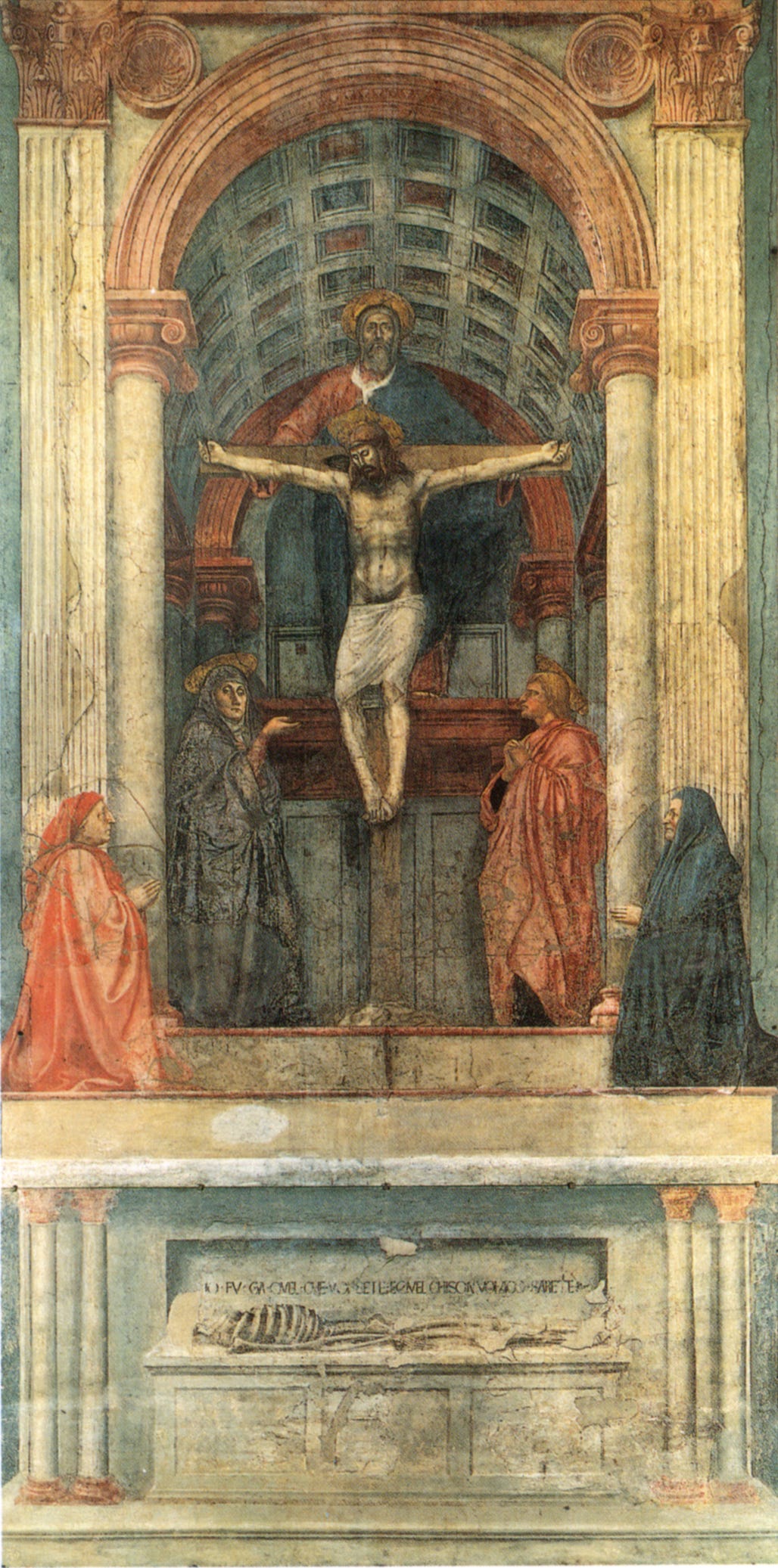

A 10-minute walk from the Baptistry you can see Masaccio’s Holy Trinity, in which God the Father is depicted within the world. He stands at the end of a long tunnel vault, painted in perspective, so a viewer standing in the right place could see the deity at the front of what looks like our earthly space, not in some distant Heaven.

Apparently for the first time in Western art, God the Father has feet. Rather than the traditional gold circlet, the two saints have halos angled in ways that suit where they’re standing. Heaven is a 3-D place, and a part of this world that we each may encounter directly. It will be another century before Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation says individuals can relate to their God without the mediation of the Catholic Church, but the idea is stirring.

Perspective wasn’t just a new understanding of space; it allowed a pictorial vision of time as well. The sculptor Donatello used perspective in a bronze panel to show the dance of Salome and the beheading of John the Baptist in a kind of sequential order, heading from rear to front so the beheading is foremost. Time is a thing that recedes, like images in a rear view mirror. (3)

Soon others would pick up on perspective, particularly after Leon Battista Alberti published “On Painting” in 1435. For some, perspective would become a mania, and a true expression of God on Earth, in the same way some of our modern thinkers believe their types of beloved math are reality itself.

Some 200 years after it first appeared in Europe, Linear Perspective also enabled the Age of Science, something we’ll get into later. It’s almost exactly the same length of time as the period beginning with standardized measurement to today. Probably a coincidence, but since we live in an era when so many technologies are “disruptive,” but it’s useful to remember that some things change the world slowly, incrementally, and in ways we never foresee.

Next up: The geometry of eternity, or, God is Math

Brunelleschi is best known today for designing and building the dome of Florence Cathedral, for centuries the largest such object in the world. Constructing it took innovations not only in building, but in new construction machines.

These may have had the greater impact on civilization. In 1471, 25 years after Brunelleschi’s death, a master artist named Andrea del Verrocchio placed a golden ball he’d cast atop the dome’s lantern. His young assistant, Leonardo da Vinci, gawped at Brunelleschi’s wondrous pulleys and platforms and winches, still on the site, and for the rest of his life filled his imagination with what else might be built.Which raises the question: Is there an Islamic take on the creation of deepfakes?

In another artwork, Donatello created an even more astonishing depiction of time.

Crucifix, Donatello, c. 1446. Basilica di Sant’Antonio, Padua. Author phot from an exhibition in Florence, 2022 This looks like a pretty standard crucifix, but Donatello is depicting the exact moment of Christ’s death. He has given his last exhalation, and his loincloth is blowing in the wind that whips Earth as the doors of Hell break so that Christ may enter and rescue the souls of the faithful

Donatello, like his friend Brunelleschi, helped engineer and participated in many of the “theatrical” events of the time, the acting out of Bible stories inside churches. Brunelleschi went so far as to design “Heaven Machinery,” enabling people dressed like angels to be lowered and lifted from the church dome, or shot over the heads of the congregation for the Annunciation to Mary. Media, entertainment, and religion have a long and deep history.