We’re not simply a civilization that numbers and counts things like no other before us. We have come to see reality itself in terms of numbers and math.* But long before all our counting, we separated things out by measuring one thing against another.

Measuring, like language, separates the bloom of reality into manageable bits. For most of the past 6000 years we measured according to the natural world. A cubit was the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. Grains were useful for both weight and space: the carat, used in the weight of both gold and diamonds, was based on the weight of a carob seed. Three kernels of barley were the length of an inch, the basis of the foot, the yard, the perch, the rod, and the furlong.

But kernels of barley vary almost fourfold in size, and carob seeds are not, contrary to Medieval belief, of a uniform weight, so there were lots of local fixes for these and other measurements. You can find niches for measuring lengths and solids on the walls of many Medieval Churches.

Time, based on the sun’s daily visit, was largely marked by changes to sand, wax candles, sundial shades, and crude mechanical clocks. The inexact divisions made for an inexact life. In his late seventeenth-century diaries, Samuel Pepys records himself frequently hanging around some powerful person’s house, waiting for them to show up. And he was trying to organize the British Navy, bedeviled by its own measurement problems.

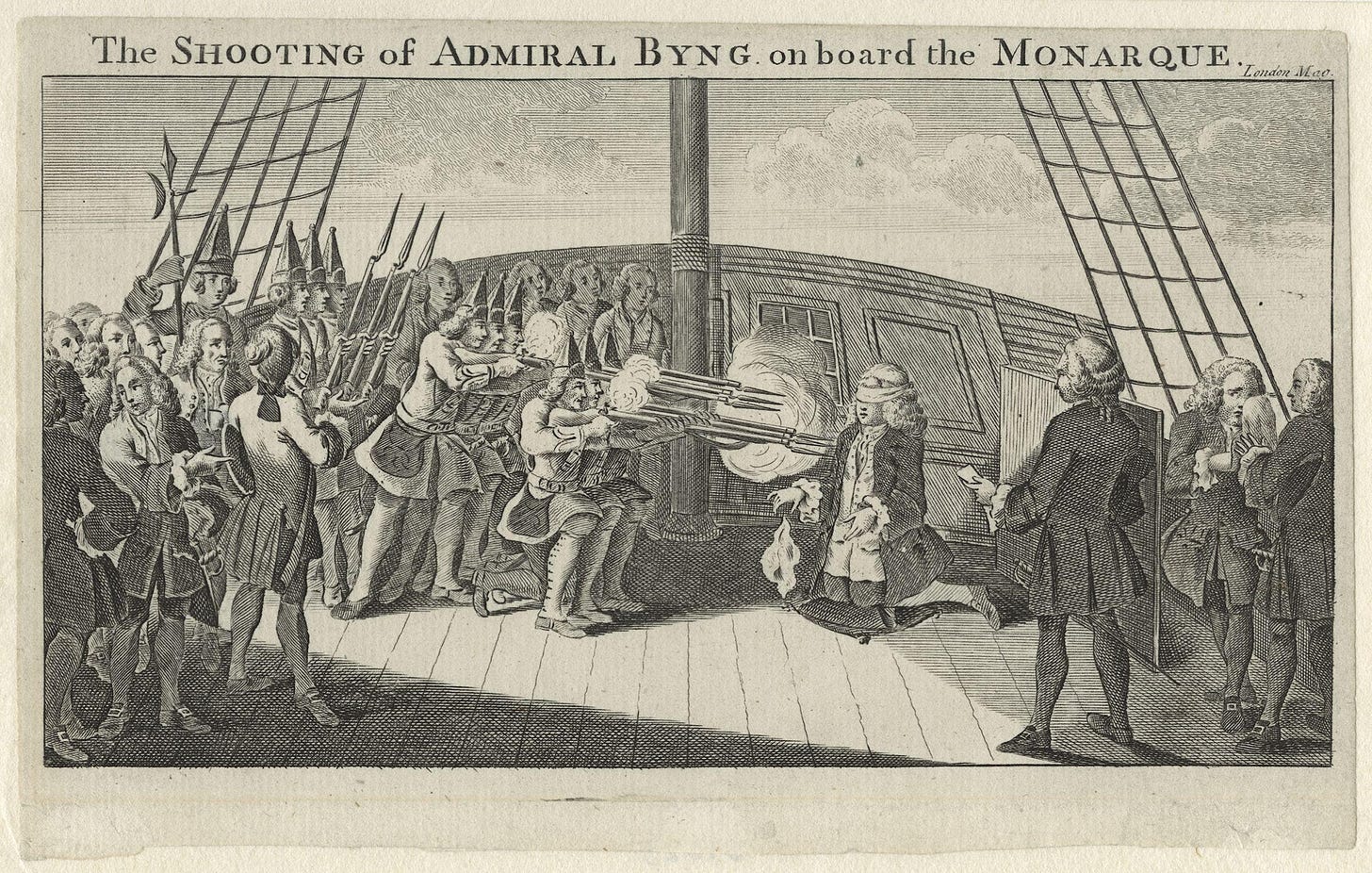

Take for example the problem of trusting and relying on naval officers who rise up not according to standard, measurable rules, but by being appointed or buying offices. Dueling was popular in the upper classes as a kind of substitute for reliability. If you are willing to die for your reputation, you will not be fearful, and can be trusted

Trust and reliability are powerful virtues. Florence and Venice figured this out way ahead of their Medieval competitors, and became international trading powers because their gold coins, the florin and the ducat, were reliably the same weight.

France was a lot slower to figure it out. Just before the Revolution there were several hundred different ways to measure things. Sharp operators made money arbitraging one measuring system against another. This is one reason the peasants got angry enough to cut off the king’s head (unlike his foot, it was not a standard for measurement.)

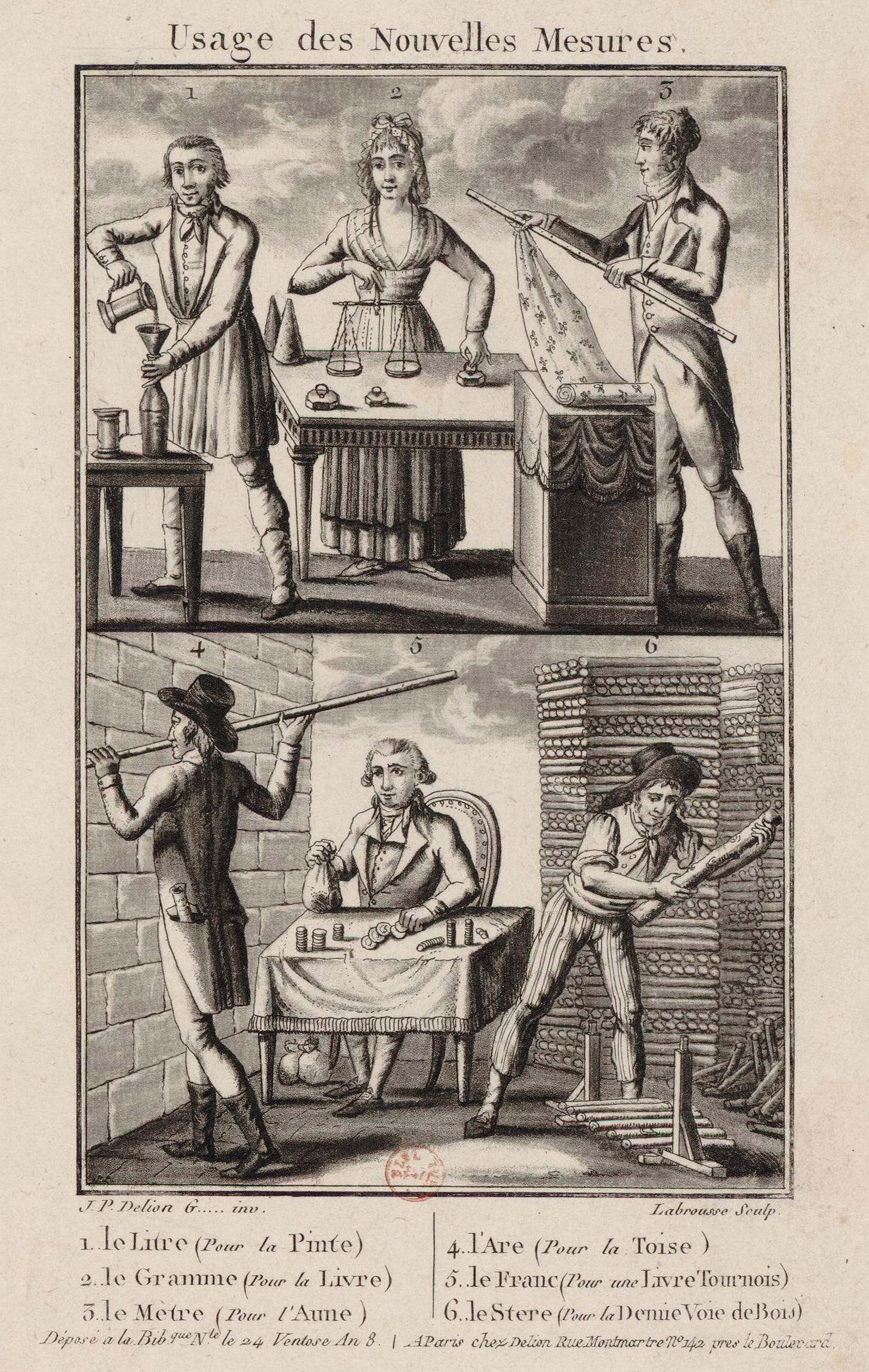

But the Revolutionaries put Reason on a pedestal. They kicked the priests out of Notre Dame Cathedral and made it a temple to Rationality. They changed the calendar to twelve 30-day months with a five-day break at the end. And they made a big show of throwing out the old ways of measurement in favor of new “rational” standards.

Length was now based on one ten-millionth of the distance from the Earth’s Pole to the Equator (a couple decades ago it was established that they were off by just 0.03%, which is pretty amazing.) Voila! Vive Le Meter! which became popular across Europe, thanks to trade.

The important takeaway of this change had nothing to do with reason, except for the rationality of standards-based growth. It didn’t matter what the measurement was based on, or even if it was divisible by 10, or 12 (important in the British System of Measures, 1824.) What mattered was that there should be one thing, unchanging, everywhere - particularly at the dawn of machine power.

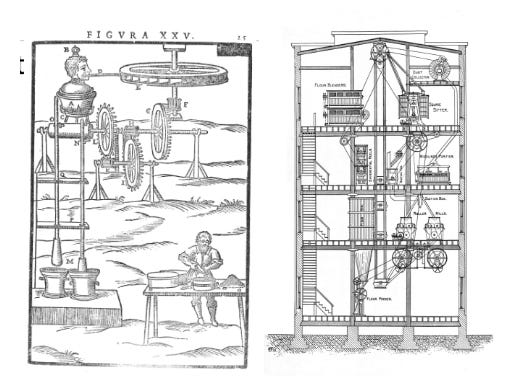

Suddenly, you could take a few rolls of paper, travel 1000 miles, and construct a factory exactly like the one back home. You could input raw materials measured to a specified size and quality, and get outputs of exactly the same taste/look/feel everywhere.

That was the really big deal: Standard measurement meant standard experience. From bread that tastes the same every time you buy it to trains made in the same way, running on dependable schedules, according to more reliable clocks. It was around this time that we also got formalized systems of military promotion, professional systems of policing, and standard rules of evidence. Deviance, in a sense, was standardized.

Standard experiences had to seem valuable, better than uneven and surprising ones. Buyers had to be persuaded that things made by the thousands and millions were special.

This revolutionized not just manufacture and distribution, but advertising, and soon branding (since these cattle have to be separated from those cattle, and marked as something different.)

Cola is fine, but it’s the branding of Coke, and the promise of a uniformly delightful experience, that makes that particular cola exceptional. I’ve had basically the same Big Mac, with the same feeling, in Connecticut, California, and Japan, decades apart. It’s kind of a staggering achievement.

And of course, when we standardized everything we changed people, too. More on that soon.

*We have a near-mystical relationship with mathematics. Maybe it’s an immaterial cosmic truth, since so much of the universe seems to obey its properties. Yet some researchers argue that numbering, along with concepts of time and space, themselves are something of a linguistic and cultural concept (here’s an interesting piece proving that, at least to some extent.)

Which, if so, throws much of our math-based understanding of the quantum world into a pretty weird place. Luckily, the quantum world likes pretty weird places.

I believe I am related to Hilda.